Deep Learning for RegEx

Recently I decided to try my hand at the Extraction of product attribute values competition hosted on CrowdAnalytix, a website that allows companies to outsource data science problems to people with the skills to solve them. I usually work with image or video data, so this was a refreshing exercise working with text data. The challenge was to extract the Manufacturer Part Number (MPN) from provided product titles and descriptions that were of varying length – a standard RegEx problem. After a cursory look at the data, I saw that there were ~54,000 training examples so I decided to give Deep Learning a chance. Here I describe my solution that landed me a 4th place position on the public leaderboard.

Disclaimer

Because this was a winning submission, I cannot share code as per CrowdAnalytix’s Solver’s Agreement. Permission is however given to share the approach to the solution.

The Problem

From the competition website, “The objective of this contest is to extract the MPN for a given product from its Title/Description using regex patterns.” Now, I didn’t know what RegEx patterns were, but I could understand the problem of extracting text from a larger text. For my purposes, given that I wanted to learn representations, it was enough for me to understand that if I had the following:

EVGA NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 Founders Edition 8gb Gddr5x 08GP46180KR

Then I just wanted to extract the MPN “08GP46180KR” using some representations that learned to distinguish MPNs from other text making up the product title and description.

Here’s the basic gist of approaching this problem using RegEx: you hard-code some rules for patterns that you are interested in finding. Here’s an example for finding e-mail addresses:

Here, this RegEx looks for pre-defined characters in fields surrounding the “@” and “.” characters. The power of Deep Learning is that, provided enough training examples, we can learn these RegEx patterns from the data directly instead of hard-coding them. This is the approach that I took.

Data Setup

The training data consisted of ~54,000 examples with the following four entries: [id, product_title, product_description, mpn]; test data was the same except for the omission of MPN field. Upon inspection of the data, I found that the MPN was, in almost all cases, present in either the product title or description, if not both. It also became evident to me that this was a hard problem as there were many other “distractors” that looked very similar to MPNs but were not marked as the target (for example, in the above Graphics Processing Unit product, “Gddr5x” looks a lot like other MPNs that existed in the training set). Given that the problem was to extract the MPN from the other fields, I set the input as a concatenation of the product title and description and set the target (or output) as the MPN.

Now that I had determined what my inputs and outputs were, I needed to determine some sort of embedding so that I could use a neural network. Because this was not a usual Natural Language Processing problem do the presence of MPN codes, HTML snippets and other odd characters, common choices such as word2vec were not going to be suitable (correct me if I’m wrong here). I fortunately had a rock-climbing buddy, Joseph Prusa, that had been working with character-wise embeddings for sentiment analysis (Prusa & Khoshgoftaar, 2014). He very kindly shared his embedding code, and after some custom-tailoring to my problem, I had an embedding solution.

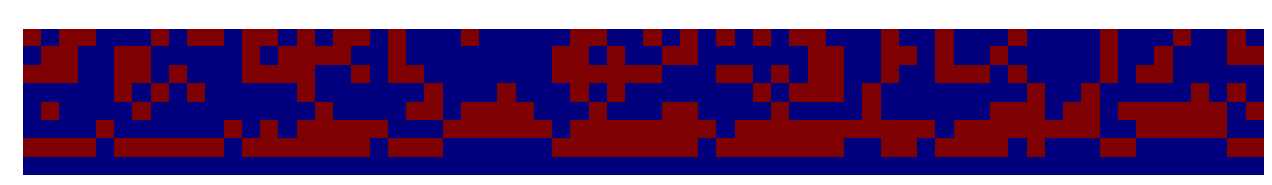

The embedding procedure takes each character and embeds it as an 8-bit binary vector. For example the string “EVGA NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 Founders Edition 8gb Gddr5x 08GP46180KR” from the above example would be represented like such:

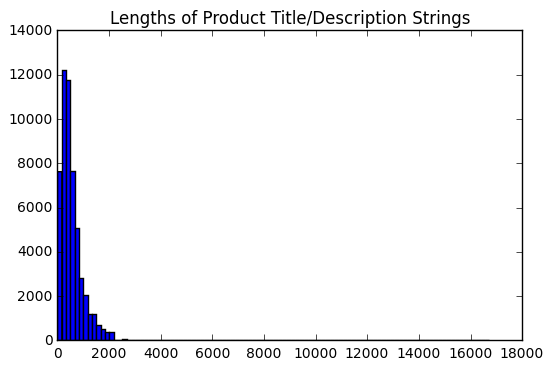

The next problem was that inputs (i.e., the concatenated product title and description string) were of varying length. Thus, I figured that I needed to settle on some way to make them all the same length to feed to the network. My first step was to visualize the distribution of all the input lengths.

Based on this distribution, I chose to set the max length to 2000 as it included most examples and avoided very long inputs to only include a couple outliers. With this max length set, I first clipped each string input and then embedded it using the procedure above. In the case that an input was shorter than the max length, it was padded with zeros. In the case that it was longer, if the MPN code was within the range of the max length, then no problem, if it was, then it was just another case where the MPN code was absent (which was very infrequent as well). The result of all this is a 8 x 2000 “image” that can now be fed to the model.

Problem Formulation

Assuming that we want to build some neural network that we can train using back-propagation, the next question is what is the appropriate output and loss function. The most natural choice seemed to be that the output would be just the MPN in the embedded vectorial format. This, in combination with a loss like Mean-Squared Error that is common of generative models in unsupervised learning just did not do the trick due to technical reasons.

Eventually I converged on the following solution that was sufficient to get some reasonable results. Namely, I defined the output of the network to be two one-hot binary vectors with a length equal to the max length (set to 2000 here), where the first vector indicated the starting index of the MPN and the second vector indicated the ending index of the MPN. Then the loss was simply the summed categorical crossentropy for both vectors.

Given this output, an auxiliary function was then created on the backend to extract the MPN vectorial representation from the input given the two indices and then convert the embedded MPN back to a string representation as the final output. In the cases where no MPN was present, the target was defined as ones at the end of both vectors.

Model Architecture

Ok, so now that the data has been embedded, and our target has been formulated, the next step was to build a model that would perform the above task well. I tried a bunch of different neural network models, including deep convolutional neural networks with standard architectures (e.g., 2D conv-net with max-pooling layers). These produced good but unsatisfactory results – nothing that was going to get me a winning spot.

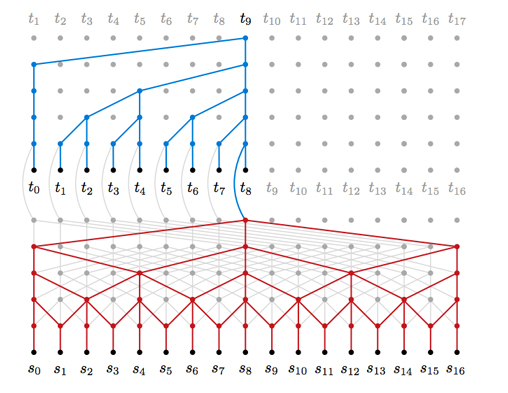

Fortunately, Google DeepMind had just put out a paper on their new model WaveNet that used causal, dilated convolutions that served as the seed of my idea. WaveNet, and other similar models, were very intriguing because they used multiple layers of convolutional operators with no pooling that were able to obtain filters with very large receptive fields while keeping the number of parameters within a reasonable range because of the dilations used at each subsequent layer (see the red portion of the figure below; image source – Neural Machine Translation in Linear Time).

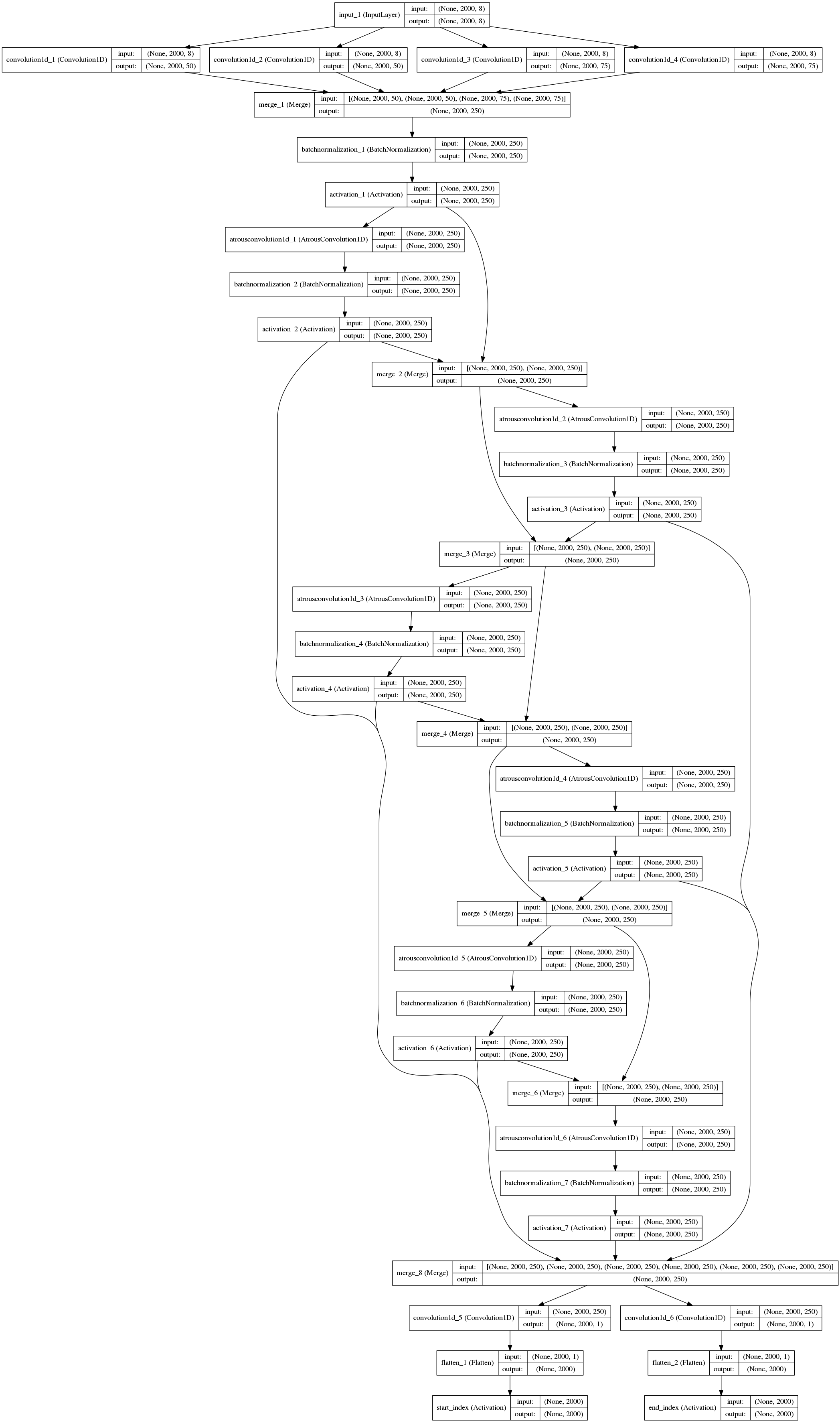

The final model idea that I converged on was to extract a set of basic features from the input, feed them through a series of dilated convolutions and then branch off two convolutional filters with softmax activation functions to predict start and end indices. In more detail, the model was as follows:

- Extract basic features from input using 1D convolutions of varying lengths (1, 3, 5, 7 with 75, 75, 50, and 50 fiters for each length, respectively); these represent single-character to multi-character representations of varying length. These representations were then concatenated and feed forward to next layers.

- Next these representations were fed through a series of blocks that perform 1D à trous (or dilated) convolutions with Batch Normalization, Rectified Linear Units, and skip connections. This allowed the network to choose the best matching start and end indices based on scopes that covered almost the entire input due to the dilated convolutions.

- Finally, two 1D convolutional filters with softmax activations were performed over the residual output; the maximum argument represented the index of highest probability for the start and end indices.

The model architecture is represented graphically below, showing the major features of the model.

Performance

After training, I observed that the model was close to perfect on the training set, hovered around ~90% accuracy for the validation set, and obtained ~84% on the public leaderboard. Not bad!

One thing that I noticed as I was scrambling to make submissions was that the model overfit the data very quickly due to the relatively small number of samples. I know that with only ~54,000 training examples, learning representations directly from the data was a bit risky, but I believe with a couple hundred thousand, my solution might have placed higher. Because I was late to the competition, I just chose to lower the learning rate and only train for a couple of epochs, which in the end worked out for me. However, provided that there was more time, I would have liked to explore some data augmentation techniques and model regularization which would have helped made the model more expressive and prevented overfitting. Additionally, pretraining on other text might have been a successful strategy. A brute-force effort would have also been increasing the max length parameter slightly, that may have given me some marginal improvements, but at a very high computational cost.

Conclusions

This was a fun challenge for me and I found it satisfying to place especially given that I had not really worked on this type of problem before. Sorry in advance for adding to the Deep Learning hype, but I found this to be another interesting application of said methods to a domain that probably doesn’t see much of these techniques used, again showing the general abilities of Deep Learning. Hope this helps someone with a similar problem.

References

- Prusa, J. D., & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. (2014). Designing a Better Data Representation for Deep Neural Networks and Text Classification.

Posted