A Response to Anti-Representationalists

Coming from a background in cognitive science, where representationalist positions are the norm, I have read literature on non-representationalist viewpoints such as Lawrence Shapiro’s “Embodied Cognition” and O’Regan’s work on Sensorimotor Theory of Consiousness to put my work in perspective. These works have not had a major impact on my research, as representations of some form still seemed necessary for many of the examples they cited. I now work daily on artificial neural networks and “deep learning” is part of my basic vocabulary. Recently, I’ve come across this article from aeon multiple times through media outlets such as Reddit and Facebook. In the essay, the much respected Dr. Robert Epstein voices his position against using computational metaphors for the brain. Here, I give my response to his, and more general claims surrounding this issue, from my background in cognitive psychology and relatively short experience conducting research in machine learning and artificial intelligence. Please share your thoughts!

Summary of The Article

The main point that Epstein attempts to convey in this article is that we are confusing ourselves about how the brain works by using our most advanced technology, computers, as a metaphor – what he refers to as the information processing (IP) metaphor. He notes that we do not have, and never develop, the components that are essential to modern day computers, such as software, models, or memory buffers. Indeed, computers process information by moving around large arrays of data encoded in bits that are then processed using an algorithm. This is not what humans do – a given. Challenging researchers in the field, he finds that basically none can explain the brain without appealing to the IP metaphor, which he reasonably sees as a problem. Crucially, he points out that the metaphor is based on a faulty syllogism whereby we conclude “…all entities that are capable of behaving intelligently are information processors”. Just as previous metaphors for the brain seem silly to us now, so will that of the IP metaphor in the future.

First Some Definitions

As with most debates, it is important to define some important terms so that disagreements are not based in semantics. The following are definitions for key terms used in Epstein’s argument and that I will reference throughout this reply. These are surely debatable, but it was the best I could do here.

-

algorithm - ”…a self-contained step-by-step set of operations to be performed”

-

operation - in mathematics, ”…a calculation from zero or more input values (called operands) to an output value.”

-

information processing - in the computing sense, ”…the use of algorithms to transform data…”

-

information - the resolver of uncertainty. we can say that data that is completely random, is uncertain, and has no information. if information of some form exists in data, it can resolve the uncertainty with respect to outputs

-

data - the quantities, characters, or symbols on which operations are performed by a computer

-

representation - from a cognitive viewpoint (which Epstein is likely to be more familiar with), is that of an “internal cognitive symbol that represents external reality”; from machine learning, ”…learning representations of the data that make it easier to extract useful information when building classifiers or other predictors.”

-

computer - ”…a device that can be instructed to carry out an arbitrary set of arithmetic or logical operations automatically.”; more generally, we can say “one that computes”

-

computation - ”…any type of calculation … that follows a well-defined model understood and expressed as, for example, an algorithm.”

These definitions were not cherry picked to support my position, and when appropriate, I gave multiple definitions to reflect use-specific cases.

Next Some Thoughts

I appreciate Epstein’s challenge to the IP metaphor and recognize the higher chance of it being invalid rather than the final answer to understanding the brain given the history of failed metaphorical applications to brain functioning. Figures such as Epstein are a necessary component to scientific progress, as we must challenge our scientific paradigms and inspect how they bias the observations we make. However, as someone that builds artificial neural networks, I (perhaps erroneously) remain convinced of the brain’s role in computation despite the evidence he and others provide. Here I attempt to illustrate how most of the examples he cites are straw man by conveying an inaccurate view of how the IP metaphor is seen by those that take seriously the primary role of computation in artificial general intelligence and its relation to the brain.

The Information Processing Metaphor

Based on our definition above, information processing involves the transformation of data using algorithms that are themselves a set of sequential operations. From this, Epstein’s understanding of how algorithms and computations relate to brain function appears immediately outdated and misguided. He strongly emphasizes that an algorithm is about the set of rules in machine code that dictates how data is stored, transfered, and received from hardware elements such as buffers, devices, and registers. Yes, this is an algorithm, but not the one that we are interested in when trying to draw connections to the brain. These aspects he highlights are details of implementation specific to conventional computers that those simulating neural nets, for example, would never argue takes place in the brain.

One aspect of his overly narrow view of computation is a veridical, discrete, and easily accessible memory store. To illustrate that we don’t have any type of memory bank like a computer, he describes a demonstration where an intern is asked to draw a dollar bill. When she must do so from memory, she is unable to draw the object with much detail. In contrast, when she is given the opportunity to look at the dollar bill, she can draw it in great detail.

“Jinny was as surprised by the outcome as you probably are…”

Not really. Besides this being the expected outcome, common findings in unsupervised learning predict that outcome, producing “fuzzy” generated images when prompted. On the other hand, the most recent state-of-the-art in generative modeling, adversarial networks, are more akin to what an artist might do – producing depictions that can be compared to reality until they match more closely (at least with respect to realism).

Even if she spent time studying the details, “…no image of the dollar bill has in any sense been ‘stored’ in Jinny’s brain.”

Artificial neural networks, and likely biological, for that matter, don’t have images stored inside them; they have abstract, identity-preserving translation-invariant, representations learned from input data. In fact, the representations themselves are a form of memory. Presumably what Jinny would be doing in those moments of studying is temporarily strengthening connections in the network hierarchy that would generate a dollar bill image. Below, we will see how this is likely distributed across the network – unlike a modern computer, yet still computational in nature.

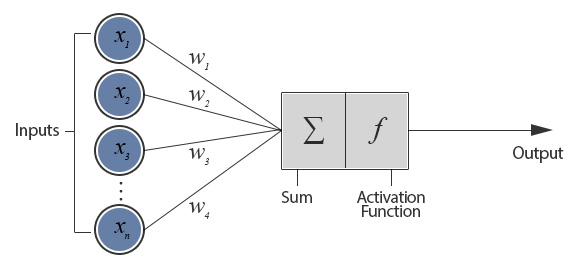

Let us adopt the general (non-spiking, feed-forward) artificial neural network (aNN) as our main example of modeling the brain from an information processing perspective. At their core, aNNs are algorithms (i.e., a sequence of operations, such as weighted sums and linear rectifiers), which are arguably biologically plausible (i.e., synapses with inhibitory and excitatory strengths that are thresholded), yet clearly limited in scope.

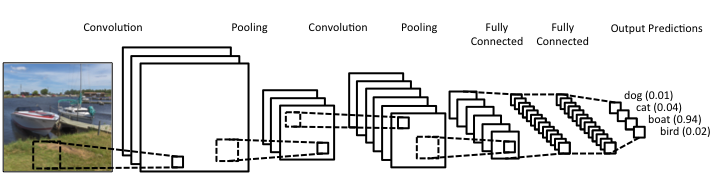

Deep neural networks, more specifically, are simply a hierarchical series of operations that take data (e.g., images analogous to retinal pattern of activation) and transform them through each layer, increasingly projecting them into a space that is more valuable for learning and making decisions. This is nothing more than an algorithm, and there is good reason to believe that it is very similar to what our brains are doing.

For example, a convolutional neural network convolves filters across an image. Certainly our brains do not perform convolutions, but rather this reflects certain assumptions that allow us to simulate them in software. Specifically, images translate across space and because we can move our heads and eyes, similar basic features can occur anywhere in the visual field. Therefore it would make sense to have similar basic features tiled across the early visual cortex with receptive fields at different locations. Indeed this is what we see in biological brains. Although an oversimplification that undoubtedly has biologically implausible limitations, it serves to make the point that these computations are abstractions of primitives (e.g., weighted sums) that can easily be physically implemented.

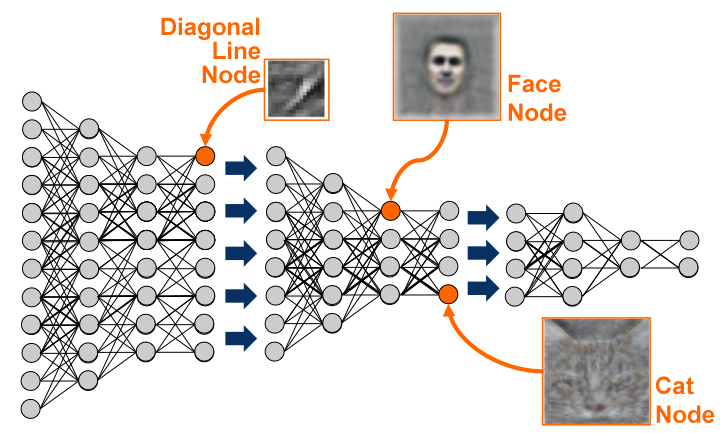

Now, in the above drawing demonstration, Epstein uses the outcome as an argument against the existence of “representations” that exist as stored memories, particularly in individual neurons. Indeed, as Epstein states and surely knows, no one in contemporary computational neuroscience would make such an absurd assertion. A very common concept in computational neuroscience is that of a sparse distributed representation, which is very similar to the idea of parallel distributed processing. In this framework, inputs can be represented with a very small number of features that are distributed. Additionally, memories (which may be representations themselves as described above) are not discrete, but are distributed. Therefore, “deleting” one memory, if even possible, may involve removing enumerable others.

From my previous blog post:

A sparse coding scheme also has logically demonstrable functional advantages over the other possible types (i.e., local and dense codes) in that it has high representational and memory capacites (representatoinal capacity grows exponentially with average activity ratio and short codes do not occupy much memory), fast learning (only a few units have to be updated), good fault tolerance (the failure or death of a unit is not entirely crippling), and controlled interference (many representations can be active simultaneously; Földiák & Young, 1995).

Thus, when we look at the deep neural network below, the image of the face or cat that points at a particular image does not mean that an “image” is stored at that location. This image was generated by synthesizing an input that maximized that unit’s activation. But because that node’s activation is contingent upon a complex weighting of all the connections before it, it would be more accurate to say that the representation is distributed across all the connections before it, not in one location. Also note that the synthesized image is fuzzy and shows that it could be insensitive to translations.

In fact, he said it himself.

“For any given experience, orderly change could involve a thousand neurons, a million neurons or even the entire brain, with the pattern of change different in every brain.”

This is exactly what neural network simulations do; this fact does not preclude computation.

A New Framework?

After this example, he attempts “to build the framework of a metaphor-free theory of intelligent human behaviour” that I find unsuccessful and only reframes the existing IP metaphor. In particular, he notes that we learn by making observations of paired (i.e., correlated) events and we are punished or rewarded based on how we respond to them. These are not new concepts to the field of machine learning and artificial intelligence. In fact, the success of almost all machine learning applications hinges on learning patterns built from correlated primitives that allow for good decisions to be made.

As an illustration he submits that when a new song is learned, instead of “storing” it, the brain has simply “changed”. It’s not clear how this is at all different. What has changed? And how? In a computer I may save a new song as a discrete file on my hard drive. But if I want a neural network to learn it and be able to generate it, the “storing” would involve changing weights distributed across the network (as stated above). For example, if I already have existing knowledge of songs, many of which have similar components, I can represent this new song as a distributed code of sparse components that is not located in one single place. These components will be coupled, thereby creating a memory (or representation) that is distributed across the very thing that perceives it and produces it.

To give a final illustration, he cites a commonly referenced example of catching a fly ball. Epstein, as well as others, argue that:

The IP perspective requires the player to formulate an estimate of various initial conditions of the ball’s flight – the force of the impact, the angle of the trajectory, that kind of thing – then to create and analyse an internal model of the path along which the ball will likely move, then to use that model to guide and adjust motor movements continuously in time in order to intercept the ball.

Now, granted that this is from a 1995 article, this is an outdated view. As someone that takes the information processing view of the brain, I would never say that catching a fly ball involves explicitly calculating trajectory. In fact, keeping the ball in constant relation to the surrounding is likely exactly what a neural network agent using reinforcement learning would learn to do if it were trained to do so based on visual input. Furthermore, it would learn representations specific to those aspects (i.e., the ball, the horizon), and ultimately be calculating trajectory implicitly. It is not clear how this could be done “completely free of computations, representations and algorithms”, as Epstein and others claim.

He argues that “because neither ‘memory banks’ nor ‘representations’ of stimuli exist in the brain, and because all that is required for us to function in the world is for the brain to change in an orderly way as a result of our experiences, there is no reason to believe that any two of us are changed the same way by the same experience.” It is just as easy to see that no experience would be the same due to distributed representations of “fuzzy” memories that have been compressed based on the existing network. IP prevails.

Conclusion

Epstein’s argument appears to be based on a erroneous, outdated, and rigid view of information processing that is unlike what those like myself take it to be. Unlike what he suggests, brains do not have perfect memory stores and representations are distributed, not local. Many simulated neural networks have exactly these features. What he has done is conflated computer with computation. Ultimately, artificial neural networks can be implemented in hardware, using the same operations as in the simulation, but without any of the other aspects involved in conventional computers, such as data transferring. Maybe if Epstein understood this, he would have to update his position.

At the closing of his essay, Epstein makes a rather insulting statement:

“The IP metaphor has had a half-century run, producing few, if any, insights along the way.”

This is a slap in the face to the fields of computational neuroscience, neuromorphic computing, and artificial intelligence, to name a few. The field of artificial intelligence, specifically, has been greatly guided by principles derived from our understanding of the brain. To ignore what those fields have to say about cognition is a dire mistake and rejecting the IP metaphor upon which they are founded removes all chance of such a dialogue.

Ultimately, I can’t explain the brain either without appealing to the IP metaphor. But it appears neither can he. I see that the IP metaphor is based on invalid reasoning, but it is the best we have to go on and amazingly deep insights have been made through it. There is also something special, and universal about IP that, at least to me, makes it seem very likely to be implemented in the brain.

“We are organisms, not computers.”

Well, maybe we’re both. At the very least we’re doing some computation. And the thing about computation is that it transcends the medium in which it is implemented – be it flesh or silicon.

Posted